This entry is part of the Summer of MeTV Classic TV Blogathon, hosted by the Classic TV Blog Association. Click here to check out this blogathon’s complete schedule.

When I was a kid, Get Smart was one show I just didn’t get. With no experience of spy or action genres, I didn’t understand what was being spoofed. In the few minutes I caught here and there, before switching to another channel, I felt mystified and vaguely annoyed.

My attitude changed completely in 1991, when Nick at Night presented a week-long marathon called Maximum Smart. Watching each night, I found the show great fun and surprisingly subversive.

There are many things to love about Get Smart–Don Adams’ approach to comedy, the wacky gadgetry, even the gorgeous cars Max drives in the opening credits. For this post, I focused on five things that I especially enjoy, as seen in Season 2’s “Island of the Darned,” which originally aired November 26, 1966. I picked this episode because it includes my favorite quote from the series (see Number 5); as a good-but-not-great episode, it also provides a good example of some elements that kept Get Smart engaging week in and week out.

1. Action tropes, spoofed

The more you’ve seen of James Bond and other 1960s spy thrillers, the more you can enjoy Get Smart‘s parody of the genre. The show’s spoofs actually go beyond the spy genre to incorporate just about every variety of action cliche that turns up in mid-century entertainment. “Island of the Darned” is based on what TV Tropes calls “Hunting the Most Dangerous Game,” a scenario in which “the villains are hunters and the hero is the prey – the game – in a formalized hunting motif.” The trope is based on the 1924 short story “The Most Dangerous Game” by Richard Connell, which has been adapted for film several times. It’s also inspired episodes on TV shows that cross a range of genres, including Star Trek, Bonanza, The Avengers, and (in a tamer form) The Partridge Family.

Hans Hunter is played by Harold Gould, who is probably best known for playing Rhoda Morgenstern’s father on The Mary Tyler Moore Show and Rhoda. His Get Smart role shows a much more youthful and vigorous side of him.

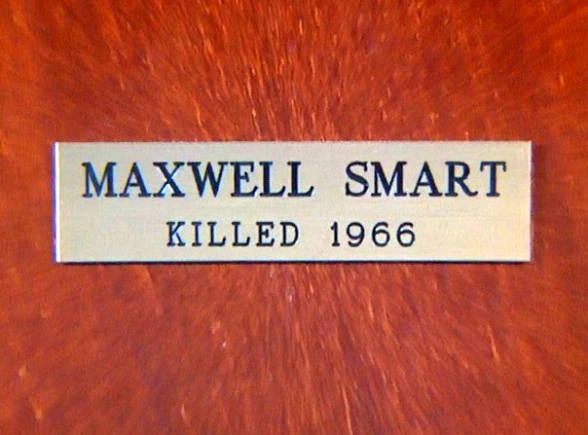

In “Island of the Darned,” KAOS operative Hans Hunter kills a CONTROL agent and has him stuffed and sent to the Chief’s office. Hunter’s goal is to lure Maxwell Smart to his island headquarters; when Max and 99 do show up there, he captures them and then offers a chance at freedom if they can elude his chase across the island until sundown.

2. Amusing Dialogue and Memorable Catchphrases

Get Smart abounds with fun exchanges. Here’s a good example from “Island of the Darned,” as the Chief fills in Hunter’s villainous backstory:

Chief: He was, at various times, a Nazi, a communist, a member of the mafia, and is right now one of the top executives of KAOS.

Max: If there’s anything I hate, it’s a joiner.

Max is also fond of what TV Tropes calls “reverse inflationary dialogue,” in which he begins with a strong statement followed up by increasingly less impressive ones. In this episode, one occurs when Max asks the Chief to send him after Hunter:

Max: Chief, you have to let me go after Hunter. I want to get that madman no matter how dangerous it is. I don’t care if he is one of the world’s greatest killers. I don’t care if he is a master of fiendish torture and death. I want him, Chief. You’ve got to let me have that assignment.

Chief: You’ve got it, Max.

Max: Of course, if you’d rather send someone else…

Chief: It’s all yours.

Max: I mean, I don’t want to force you into anything, Chief.

Max’s famous “Would you believe?” routine is his ultimate example of reverse inflationary dialogue and represents one of the many catchphrases the show popularized. In this episode it comes just after Hunter captures Max and 99, as Max tries to convince the villain that backup is on the way. Hunter’s only response throughout is increasingly maniacal laughter.

Max: In a very short while, General Crawford and a hundred of his crack paratroopers will come crashing into this landing.

Would you believe J. Edgar Hoover and 10 of his G-men?

How about Tarzan and a couple of his apes?

Bomba the jungle boy?

Some of this episode’s jokes are obvious but still somehow amusing. When Hunter challenges Max to a game of Russian roulette, Max asks if they couldn’t switch to checkers.

This week’s secret weapon from the CONTROL crime lab is a set of “bazooka butts,” grenades disguised as cigarettes. Max is told that if he fails to release the cigarette in time, it will blow a hole in the back of his head the size of a basketball; he inevitably replies, “Well, that’s one way to quit smoking.”

More unexpected is this exchange–it’s not exactly PC by modern standards, but I’m surprised it made it to the air at all in 1966:

Hunter: As you can see, Mr. Smart, my trophy collection includes one of almost every kind of animal…except one. You—a homo sapien.

Max (indignant): Now just a minute, Hunter. I’m as normal as you are.

3. Bureaucratic Inanities

Perhaps because my career history includes time in a government setting, I find myself tickled by the mundane bureaucratic details that bog down the battle between CONTROL and KAOS.

In this episode, the courier delivering the package that contains Agent 27’s stuffed body insists on getting a real signature on his form–“The Chief” won’t do.

I especially enjoy the courier’s parting remarks:

Delivery Man: I’ve delivered a lot of packages in my time, some here to CONTROL and some over to KAOS headquarters, and I’ll tell you this: Crime may not pay, but it sure tips a lot better.

4. Agent 99

Barbara Feldon’s Agent 99 is an admirable example of a smart, hard-working, courageous woman by the standards of the time. American TV was apparently not ready for a true female badass like The Avengers‘ Emma Peel, so 99 spends a lot of time showing off her feminine side. In this episode, she screams when Agent 27’s body is revealed, and during the long outdoor chase scenes, she occasionally whines about her ability to go on (although she does keep going).

As usual, she also spends a lot of time juggling the need to keep Max on track with her wish to protect his ego.

Still, it’s always clear that 99 is more intelligent and competent than her partner (admittedly, not a high bar). At this episode’s climax, she has to prod him several times before he remembers the existence of the Bazooka butts, the weapon that saves their lives.

We don’t get to see much of 99’s fun 1960s fashions in this episode, which she spends mostly in a safari suit as she runs through woods and slides down hills. (Actually, that doesn’t look much like Barbara Feldon sliding down that hill, does it?)

5. A Strain of Subversion

My favorite thing about Get Smart is the mildly subversive nature of a show produced at the height of the cold war that made the cold war look ridiculous. Most likely, show co-creators Mel Brooks and Buck Henry set the tone. Brooks explained in 1965, “It’s a show in which you can comment, too. I don’t mean we’re in the broken-wing business. We’re not social workers, but we can do some comment such as you can’t inject in, say, My Three Sons.”

This episode’s script (which Henry had a hand in writing) ends with my favorite exchange from the series. It takes place just after gets blown up.

99: Oh, Max, how terrible.

Max: He deserved it, 99. He was a KAOS killer.

99: Sometimes I wonder if we’re any better, Max.

Max: What are you talking about, 99? We have to shoot and kill and destroy. We represent everything that’s wholesome and good in the world.

This is a pretty bold line for mainstream TV at a time when the Vietnam War was still escalating. (I must not have been the only one who liked the line because it showed up again, in a slightly different form, in the 1989 reunion movie Get Smart, Again!)

I hope this brief celebration of Get Smart whets your appetite to watch the show on MeTV this summer. And I hope you let me know your favorite things about the series!

Some of my other posts related to shows on MeTV’s summer schedule:

H.R. Pufnstuf and the Best School Library Book Ever

Alice: An Appreciation (The Brady Bunch)

Everything is Gray: Five Moral Lessons from Naked City

The Twilight Zone and Alfred Hitchcock Presents: Family Affair Connections, Part 1